I was better at making money when I was 8 than I am at 32. That's not to say I made more money then (though I admit, the gap isn't quite as big as I hoped it would be by this point) but rather that money seemed to come easier when I was a kid than it does now.

In retrospect, my circumstances were kind of perfect for financial success (read: I was very privileged.) I carefully avoided debt in the first few years of life. All my basic living expenses were taken care of. Two nice people I called Mom and Dad often gave me an allowance when I did extra chores. Greeting cards routinely carried a couple unmistakable grams of extra weight.

But when my younger brother Andrew and I wanted something that was a financial stretch for us, like a stereo for our room (to play "Tubthumping" by Chumbawamba) or a pair of walkie talkies (to speak to each other from 80 feet away), we would pursue our goal with an entrepreneurial spirit and an unusual vigor. We'd start, of course, where any promising enterprise begins: by making an oversized fundraising thermometer on a poster board, like we saw on TV and in the movies¹. Then, we'd outline a plan detailing how we'd generate the necessary funds.

Here are just a handful of the many ways that we filled up those fundraising thermometers. Please keep in mind that all of these endeavors took place between the ages of 7 and 10, or as I like to call them, my peak earning years:

Unsanitary Candy Production

The first time Andrew and I saw Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, we were so enamored by the mysterious business success story that we turned it off before it was finished (missing the lessons on gluttony, greed, etc.) so that we could build our own candy-making empire with a few friends. Grabbing whatever we could from the kitchen, we mashed confectionary elements together to sell door-to-door. We made it to exactly one house, where a discerning man pointed out that our operation didn't look quite clean enough to buy from. That stinging feedback was enough to kill our momentum and shutter the business. Rather than reflect on our flawed manufacturing processes, we blamed our failure on a lack of Oompa Loompas, who seemed to do all the work in the movie.

Fishing for Cash

Mom, Dad, Andrew, and I were enjoying a peaceful morning in a canoe on a small pond in neighboring Vermont. For some reason, we had a fishing rod. I say "for some reason" because nobody in our family, least of all me, had any interest in fishing. I was staring idly at the water when I saw, like a vision, a wad of cash on the bottom of the pond. I excitedly told my parents. "Adam, for one hour, will you stop thinking about money?" they scolded. Then they saw it for themselves. Andrew and I spent the next 15 minutes rigging the fishing rod to very carefully lift the cash out of the water. Some dropped and was unrecoverable, but we came up with about $50, which we instantly put into Microsoft stock. OK, no. We probably spent it on Beanie Babies or Pokémon cards. Regardless, the found money gave us unrealistic expectations for all future water outings.

First Grade Publishing Co.

In the first grade, my class made our own books. It was a big production. We did the writing, the illustrations, and even got them bound. Rather than simply enjoy the final product and the sense of a job well done, I rallied some of my classmates to sell our works later that week at a community cookout. When the cookout came, though, our effort fizzled, as my friends were more interested in competing in the three-legged race and eating cheeseburgers than they were in hawking our books to strangers.

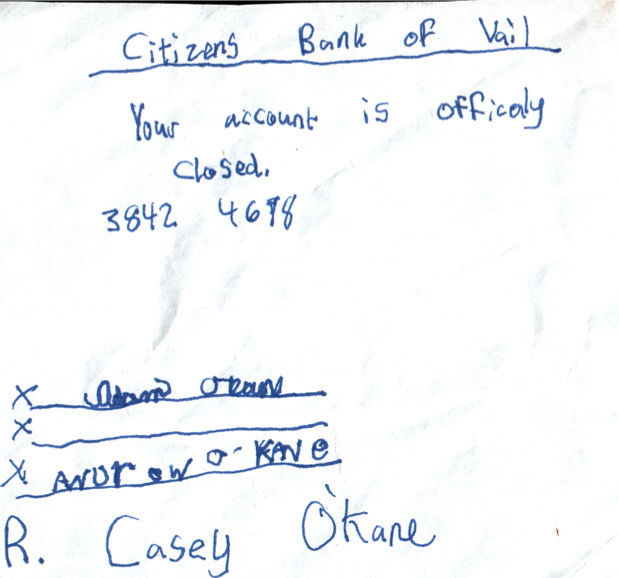

The Bank of Vail

While on a ski vacation with our Dad's side of the family (a setup that, I know, won't help me position myself as a scrappy young hustler) Andrew and I were so desperate to even hold money that we opened a bank that we dubbed The Bank of Vail. We loved everything about it. The feeling of our uncles' cash in our hands, the tallying of account balances, the grave responsibility of keeping the sums secure (though I should mention that we were a non-FDIC institution.) We were totally aware the money wasn't ours — it just made us feel rich². On the last day of the trip, though, when it was time to close our customers' accounts, our uncle Casey gave us a tough lesson in banking when he explained what interest was. We paid him what was, in hindsight, an exorbitant rate, and decided our future was not in finance.

Lemonade...and More

Running a lemonade stand is a vital rite of passage for kids growing up in suburban America. Fancying ourselves as more advanced child entrepreneurs, Andrew and I took it up a notch and expanded our menu. We bought snacks and drinks in bulk at Sam's Club (and in that, learned about COGS), acquired a small hotplate at a yard sale down the street for the suspicious price of $2, picked up a couple packs of frozen hot dogs, and convinced our Mom to move her car (so we could use its power source and give our business an air of legitimacy) to the curb of the empty lot next door, which was closer to a small intersection. There was about 50% more traffic at this location (3 cars per hour) than there was at our house (2 cars per hour) and as we knew, location was everything. We also used a speaker and microphone to ensure that our neighbors knew about our offerings.

ClearVue

Our main hustle, the one we returned to over and over, was selling a glass cleaner called ClearVue. It was our Dad's business — the product was on the shelves in a handful of glass shops in New England for years, and then he brought it to grocery stores in the region and then all around the country. It was a cool story.

When I was 10, I started buying the product from Dad wholesale and selling it by the case. I'd open the phonebook, dial local businesses, ask to speak to the right person, and try to make the sale. My success rate was low, but I got ClearVue in an office supply store, an inn, a limo company, restaurants, and more.

A couple years before that point, when we were a little less sophisticated, Andrew and I set out to sell door-to-door on a hot summer afternoon. We searched our house, grabbed every ClearVue bottle we could find (topping off the partially-filled ones with water), loaded them into our wagon, and hit the road. We knocked on door after door, fielding questions about ClearVue's environmental impact, what stores it could be purchased in, how it compared to Windex³, and where our parents were.

Nearing the end of our journey (about a half mile from our house) we knocked on the door of a woman we didn't know. She patiently listened to our pitch, then instructed us to wait right there. We assumed she was inside deliberating with her husband, weighing whether they could afford to spend $3 on a bottle of glass cleaner — but she returned a moment later, telling us that she had called the police, and that they would be there soon. She thought that we were lost and that she was helping us, but in reality, she had blown up what was shaping up to be a fantastic sales day, and we instantly hated her. Just then, Dad walked up the street and took us home, and we avoided an encounter with law enforcement. He didn't avoid an encounter with Mom, though, who hadn't been home when we left.

***

This quest for the almighty dollar evolved with age. Andrew and I both got our first "real jobs" early in our high school years. In college and since, I've certainly not taken the path that I could've if I was optimizing solely for income. Fishing $50 out of the pond in Stowe and grilling on that shoddy hotplate seem like a lifetime ago. But every time I drive by a lemonade stand, I stop for a cup, and I overpay. Because I remember how it was. And the wondrous thrill, as a kid, of making a buck.

¹Our most ambitious goal ever was to save $1,000 to buy the least expensive golf cart available at a nearby dealership, but alas, we came up way short. Note that we had no intention of using this golf cart on a golf course, but rather driving it around our neighborhood.

²Before going on the ski trip, Andrew, then 6, had the bank exchange the $70 he had saved up into 70 $1 dollar bills, because it felt like a larger total, and he liked holding it. For the same reason, I think he refused to actually spend (and part with) the money when we got to Colorado.

³Windex was firmly entrenched in our heads as the primary source of evil in the world. It was like Shredder from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, then Hitler, then the villainous scoundrel who we imagined ran Windex. I knew, even at 8, that Windex was just a subsidiary of S.C. Johnson & Son, and I imagined those guys to be even worse. Every time we went to the grocery store, Andrew and I made sure to move ClearVue in front of the Windex bottles. (Dad didn't endorse any of this, of course, but he didn't have to.) And even though ClearVue hasn't been on the shelves for 20 years, I've still never used Windex — and I never will.

Thanks for reading! This is the second of five stories I’m going to do between now and the end of June. If you liked this one, please subscribe below, and you’ll receive them in your inbox.

Love this, Adam. I think I remember a brief career in law enforcement, too?